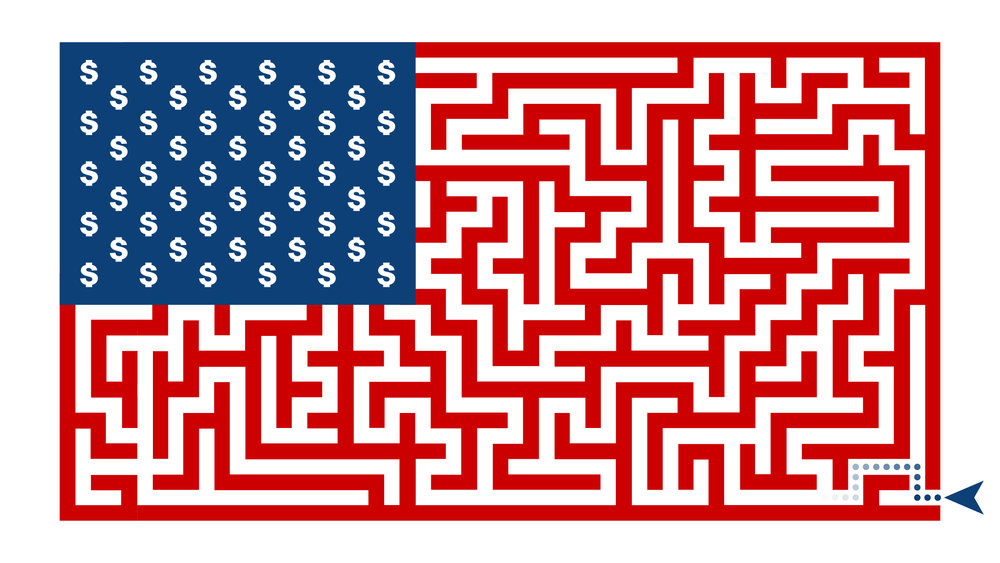

For many Americans, the financial landscape is uncertain terrain. We’re worried about whether Social Security will still exist when we retire, saving up for a rainy day, and financing the ballooning costs of a college education. But for the 23.2 million known unbanked people in the U.S. the journey to economic stability is an even more difficult maze. Among this population are many of the 11 million undocumented residents estimated to be in this country, including “Dreamers” or undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. as children.

Despite the current political debate, most undocumented immigrants did not arrive in the U.S. illegally. According to the Center for Migration Studies, 42 percent of all undocumented residents in 2014 were “overstays,” those living in the U.S. on expired visas. Under the Naturalization Act of 1952, living in the country under an expired visa isn’t a crime. As of last year, nearly 690,000 young immigrants were enrolled in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, according to the Pew Research Center. These DACA recipients have the legal right to work and attend school.

But those bare-bones legal protections don’t necessarily make life easier from a financial perspective. From trying to find a steady job (and a way to cash paychecks) to worrying about keeping cash secure in the home, the undocumented and unbanked can spend hundreds more a year and tack on immeasurable stress trying to make do without common financial tools.

Getting a job is hard work

Finding a job is often the first—and biggest—financial hurdle undocumented residents face. Under the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, employers can’t knowingly hire undocumented workers. They’re legally required to ask for documentation proving that someone is authorized to work in the U.S. However, if an undocumented worker is hired, the worker can’t be fired based on a failure to produce documentation later, as stated in the Immigration and Nationality Act.

Undocumented workers do find jobs, just not great ones. Typically they end up in fields like construction, farm labor, or the service industry, essentially jobs with high turnover and employers eager to fill positions quickly. Often, as an Eater exposé found, workers in the service industry submit false documents while employers turn a blind eye, unable to afford the cost of verifying every employee. In some cases, employers may simply choose not to verify employees at all, opting to take the risk and pay the fine if caught.

Adina Appelbaum, an immigration attorney and founder of the website Immigrant Finance, says that most undocumented workers “are forced to take jobs under the table, where they are more likely to face poor work conditions and abuse from employers.”

A recent report from the University of California, Davis and Samuel Merritt University also found immigrant workers often find themselves in “3-D jobs—dirty, dangerous, and demanding (sometimes degrading or demeaning).” Working longer hours for less pay, immigrant workers are some of the most vulnerable members of the workforce, often facing risky environmental exposure, a lack of proper training, and insufficient safety equipment.

The undocumented also have a greater fear than just being fired for speaking up about poor working conditions—they risk their estranged employer retaliating by contacting immigration authorities or otherwise drawing attention to their status. Some undocumented employees may not seek treatment if injured on the job for these reasons.

If undocumented workers do find themselves on the radar of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement or taking a wayward employer to court, their legal bills could pile up fast. Appelbaum, who has worked with several undocumented residents facing deportation, says that because they don’t have legal status, the undocumented don’t have rights to government-appointed counsel in court, meaning they must self-fund or rely on pro-bono legal representation.

Too much cash and not enough security

Even if the undocumented are able to find decent employment, cashing those paychecks can be an expensive and stressful process.

First, there’s the language barrier. Native Spanish speakers made up the majority of undocumented immigrants in 2016 according to the Pew Research Center. However, a 2015 Nielsen review of the top 10 Spanish language ads among Hispanics found only one was for a financial institution. And while many institutions emphasize hiring bilingual customer service representatives and reaching the growing English as a Second Language population, not all branches offer those services. Things get bleaker for undocumented immigrants from other nations. While some financial institutions offer additional languages—like Charles Schwab’s Chinese-language service—many stop at Spanish, especially in smaller, local branches.

There’s also the issue of discrimination. GE Capital Retail Bank was fined $169 million dollars in 2014 for engaging in discriminatory practices after the bank sent out information about a debt-reduction program but failed to mail offers to those who had indicated they wanted communications in Spanish, or who had mailing addresses in Puerto Rico. In 2017, a federal judge ruled Wells Fargo could be sued under an anti-discrimination law from the 1800s after many DACA recipients claimed the bank denied their student loans or credit products on the basis of their immigration status.

Undocumented residents also face an uphill battle with financial education and sometimes fear entering the financial system altogether. Andrew Wang, a managing partner at Runnymede Capital Management and a former bank worker, recalls very few undocumented residents coming into his branch. “Because policies vary from bank to bank, the undocumented may not know the types of documents they need to open an account,” he says. “Many [banks] accept an ITIN [Individual Taxpayer Identification Number], which is available to those working legally in the U.S., including their spouses and dependents. Some even accept a passport and country of issuance.”

Javier Gutierrez, a DACA recipient and founder of the website Dreamer Money, recalls that when he was growing up, his parents rarely relied on a bank. “They had little access to financial services in Spanish, and I don’t think they knew they needed them,” he says.

According to Gutierrez, his parents’ life in Mexico—where corruption is common in many sectors—prior to arriving in the U.S. contributed to a general distrust of financial institutions. They “used cash for everything, and they kept their savings inside of a flannel shirt in the closet,” he says.

Keeping cash savings at home presents another kind of risk. While those with bank accounts can rely on loss protection to replace stolen checking account funds, the unbanked often have no recourse if their money is lost or stolen, aside from going to the police, which is a dicey proposition for many undocumented immigrants.

As a “Dreamer” who falls into the hazy area of undocumented, Gutierrez went a different route as a young adult, learning the ropes of the U.S. financial system and securing a basic bank account. But he still had another hurdle to face: access to a branch location. “I didn’t have a car before and during college, so sometimes it was easier to cash a check at the gas station,” he says.

Without access to a bank, many undocumented workers rely on check-cashing stores or outlets at businesses like gas stations to access their cash. These locations are the “cheapest” options, normally tacking on a per-transaction fee of up to $10. Payday loan fees can go as high as 10 percent for check cashing. Other offenders include big banks and some credit unions, which charge fees ranging from around an $8 flat rate to 1 percent of the check amount.

More than $54 billion is sent abroad by immigrants each year, according to The Hill. For those who send money to family and friends internationally, places like Western Union and MoneyGram charge service fees that eat into their hard-earned cash. While most fees hover around the $5 mark, depending on the destination they can also exceed $50.

Spend, Save, and Invest For Your Future and a Greener World

Join Aspiration today to put your money where your values are.

Learn More About AspirationSeeking alternatives

Though many undocumented immigrants struggle with their unbanked status, they also find canny workarounds to get on solid financial footing, like community-based loan groups, purchasing property, or starting businesses.

“Many work hard to save the money and often give it to their families,” Appelbaum says. “They also tend to distribute and share their money among close friends who are in need of help, creating an informal collective banking system.”

Lending circles, where money is collected into a pool and distributed to the neediest members, help unbanked immigrants start businesses, cover financial and medical emergencies, and manage their daily lives. While many lending circles are informal collections among family and friends or neighbors, nonprofits are also helping facilitate and grow lending circles into a bigger financial service.

Mission Asset Fund, based in San Francisco, provides financial literacy classes and financial services to immigrants and the Latino community. Over the last few years, the group has also grown its lending circle program to mirror the benefits one might find at a traditional bank. Today, the lending circles include six to 12 people contributing toward loans of up to $2,400. Every month, a new member can receive a loan (ensuring everyone has a chance to participate). Loan holders repay on a monthly basis, and Mission Asset Fund reports payment information to the credit bureaus—helping recipients build their credit in the process.

The fund’s mission isn’t just to help members find the financing they need but to help them learn to advocate for themselves. Miguel Castillo, client success manager at Mission Asset Fund and a DACA recipient, found that it was important to create a level of trust among his clients. “Many are too scared to go into banks themselves,” he says. “Even if I translate the financial jargon for them, many still don’t understand why they need to know certain aspects like credit scores or just navigating the financial system in general.”

There are other methods being tested to help unbanked populations. PayPal is partnering up with smaller banks to offer debit cards and services like direct deposit connected to PayPal accounts, which require just your legal name and an email address to register.

Gutierrez created his website specifically to help Dreamers navigate the complexities of the U.S. financial system. He’s been able to pay off around $34,000 in student loan debt and believes that with the right information, others can do the same. His site offers informative posts on building credit, choosing a bank or credit union, and buying a home, all targeted toward those who have temporary or uncertain immigration status.

While the current political climate has heightened uncertainty around immigration, nonprofits and people like Gutierrez are helping to bring a new, brighter financial future for undocumented residents.

Pingback: How To Carve Out A Meaningful Career - Beyond The Dollar - Deep and Honest Conversations About How Money Affects Our Well-Being